Desire is infinite, its fulfilment limited. Desire is unlimited in everyone; the power of fulfilment varies.

- Thus some are more successful than others in life.

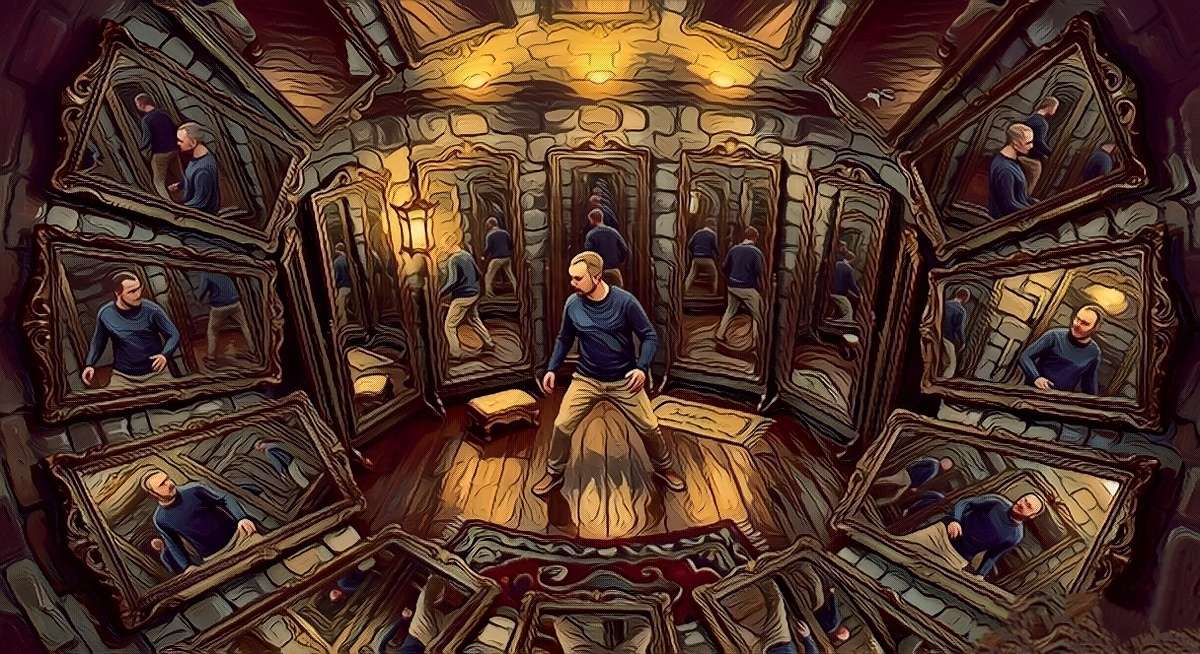

2. This limitation is the bondage we are struggling against all our lives.

3. We desire only the pleasurable, not the painful.

4. The objects of desire are all complex — pleasure-giving and pain-bringing mixed up.

5. We do not or cannot see the painful parts in objects, we are charmed with only the pleasurable portion; and, thus grasping the pleasurable, we unwittingly draw in the painful.

6. At times we vainly hope that in our case only the pleasurable will come, leaving the painful aside, which never happens.

Our desires also are constantly changing — what we would prize today we would reject tomorrow. The pleasure of the present will be the pain of the future, the loved hated, and so on.

8. We vainly hope that in the future life we shall be able to gather in only the pleasurable, to the exclusion of the painful.

9. The future is only the extension of the present. Such a thing cannot be!

10. Whosoever seeks pleasure in objects will get it, but he must take the pain with it.

11. All objective pleasure in the long run must bring pain, because of the fact of change or death.

12. Death is the goal of all objects, change is the nature of all objective things.

13. As desire increases, so increases the power of pleasure, so the power of pain.

14. The finer the organism, the higher the culture — the greater is the power to enjoy pleasure and the sharper are the pangs of pain.

15. Mental pleasures are greatly superior to physical joys. Mental pains are more poignant than physical tortures.

16. The power of thought, of looking far away into the future, and the power of memory, of recalling the past to the present, make us live in heaven; they make us live in hell also.

17. The man who can collect the largest amount of pleasurable objects around him is as a rule too unimaginative to enjoy them. The man of great imagination is thwarted by the intensity of his feeling of loss, or fear of loss, or perception of defects.

18. We are struggling hard to conquer pain, succeeding in the attempt, and yet creating new pains at the same time.

We achieve success, and we are overthrown by failure; we pursue pleasure and we are pursued by pain.

20. We say we do, we are made to do. We say we work, we are made to labour. We say we live, we are made to die every moment. We are in the crowd, we cannot stop, must go on — it deserves no cheering. Had it not been so, no amount of cheering would make us undertake all this pain and misery for a grain of pleasure — which, alas, in most cases is only a hope!

21. Our pessimism is a dread reality, our optimism is a faint cheering, making the best of a bad job.

First of all, try to understand this: Does man make laws, or do laws make man? Does man make money, or does money make man? Does man make name and fame, or name and fame make man?

Be a man first, my friend, and you will see how all those things and the rest will follow of themselves after you. Give up that hateful malice, that dog-like bickering and barking at one another, and take your stand on goal purpose, right means, righteous courage, and be brave When you are born a man, leave some indelible mark behind you.

You must remember the one theme that runs through all the Vedas: “Just as by the knowledge of one lump of clay we know all the clay that is in the universe, so what is that, knowing which we know everything else?” This, expressed more or less clearly, is the theme of all human knowledge. It is the finding of a unity towards which we are all going. Every action of our lives — the most material, the grossest as well as the finest, the highest, the most spiritual — is alike tending towards this one ideal, the finding of unity. A man is single. He marries. Apparently it may be a selfish act, but at the same time, the impulsion, the motive power, is to find that unity. He has children, he has friends, he loves his country, he loves the world, and ends by loving the whole universe. Irresistibly we are impelled towards that perfection which consists in finding the unity, killing this little self and making ourselves broader and broader. This is the goal, the end towards which the universe is rushing. Every atom is trying to go and join itself to the next atom. Atoms after atoms combine, making huge balls, the earths, the suns, the moons, the stars, the planets. They in their turn, are trying to rush towards each other, and at last, we know that the whole universe, mental and material, will be fused into one.

The process that is going on in the cosmos on a large scale, is the same as that going on in the microcosm on a smaller scale. Just as this universe has its existence in separation, in distinction, and all the while is rushing towards unity, non-separation, so in our little worlds each soul is born, as it were, cut off from the rest of the world. The more ignorant, the more unenlightened the soul, the more it thinks that it is separate from the rest of the universe. The more ignorant the person, the more he thinks, he will die or will be born, and so forth — ideas that are an expression of this separateness. But we find that, as knowledge comes, man grows, morality is evolved and the idea of non-separateness begins. Whether men understand it or not, they are impelled by that power behind to become unselfish. That is the foundation of all morality. It is the quintessence of all ethics, preached in any language, or in any religion, or by any prophet in the world. “Be thou unselfish”, “Not ‘I’, but ‘thou’” — that is the background of all ethical codes. And what is meant by this is the recognition of non-individuality — that you are a part of me, and I of you; the recognition that in hurting you I hurt myself, and in helping you I help myself; the recognition that there cannot possibly be death for me when you live. When one worm lives in this universe, how can I die? For my life is in the life of that worm. At the same time it will teach us that we cannot leave one of our fellow-beings without helping him, that in his good consists my good.

We can very much agree as to principles, but not very much as to persons. The persons appeal to our emotions; and the principles, to something higher, to our calm judgement. Principles must conquer in the long run, for that is the manhood of man. Emotions many times drag us down to the level of animals. Emotions have more connection with the senses than with the faculty of reason; and, therefore, when principles are entirely lost sight of and emotions prevail, religions degenerate into fanaticism and sectarianism. They are no better than party politics and such things. The most horribly ignorant notions will be taken up, and for these ideas thousands will be ready to cut the throats of their brethren. This is the reason that, though these great personalities and prophets are tremendous motive powers for good, at the same time their lives are altogether dangerous when they lead to the disregard of the principles they represent. That has always led to fanaticism, and has deluged the world in blood. Vedanta can avoid this difficulty, because it has not one special prophet. It has many Seers, who are called Rishis or sages. Seers — that is the literal translation — those who see these truths, the Mantras.

The main difference between men and the animals is the difference in their power of concentration. All success in any line of work is the result of this. Everybody knows something about concentration. We see its results every day. High achievements in art, music, etc., are the results of concentration. An animal has very little power of concentration. Those who have trained animals find much difficulty in the fact that the animal is constantly forgetting what is told him. He cannot concentrate his mind long upon anything at a time. Herein is the difference between man and the animals — man has the greater power of concentration. The difference in heir power of concentration also constitutes the difference between man and man. Compare the lowest with the highest man. The difference is in the degree of concentration. This is the only difference.

Everybody’s mind becomes concentrated at times. We all concentrate upon those things we love, and we love those things upon which we concentrate our minds. What mother is there that does not love the face of her homeliest child? That face is to her the most beautiful in the world. She loves it because she concentrates her mind on it; and if every one could concentrate his mind on that same face, every one would love it. It would be to all the most beautiful face. We all concentrate our minds upon those things we love. When we hear beautiful music, our minds become fastened upon it, and we cannot take them away. Those who concentrate their minds upon what you call classical music do not like common music, and vice versa. Music in which the notes follow each other in rapid succession holds the mind readily. A child loves lively music, because the rapidity of the notes gives the mind no chance to wander. A man who likes common music dislikes classical music, because it is more complicated and requires a greater degree of concentration to follow it.

If X is unknown, then any qualities we give to it are only derived from our own mind. Time, space, and causation are the three conditions through which mind perceives. Time is the condition for the transmission of thought, and space for the vibration of grosser matter. Causation is the sequence in which vibrations come. Mind can only cognise through these. Anything therefore, beyond mind must be beyond time, space, and causation.

There is no good, and there is no evil. God is all there is . . . . How do you know what is good? You feel [it]. [How do you know what is evil ? If evil comes, you feel it. . . . We know good and evil by our feelings. There is not one man who feels only good, happy feelings. There is not one who feels only unhappy feelings. . . .

Want and anxiety are the causes of all unhappiness and happiness too. Is want increasing or decreasing? Is life becoming simple or complex? Certainly complex. Wants are being multiplied. Your great-grandfathers did not want the same dress or the same amount of money [you do]. They had no electric cars, [nor] railroads, etc. That is why they had to work less. As soon as these things come, the want arises, and you have to work harder. More and more anxiety, and more and more competition.

It is very hard work to get money. It is harder work to keep it. You fight the whole world to get a little money together [and] fight all your life to protect it. [Therefore] there is more anxiety for the rich than for the poor. . . . This is the way it is. . . .

When the world is the end and God the means to attain that end, that is material. When God is the end and the world is only the means to attain that end, spirituality has begun.

Beggar’s love is no love at all. The first sign of love is when love asks nothing,

when it] gives everything.

The second [angle of the triangle of love] is that love knows no fear. You may cut me to pieces, and I [will] still love you. Suppose one of you mothers, a weak woman, sees a tiger in the street snatching your child. I know where you will be: you will face the tiger. Another time a dog appears in the street, and you will fly. But you jump at the mouth of the tiger and snatch your child away. Love knows no fear. It conquers all evil. The fear of God is the beginning of religion, but the love of God is the end of religion. All fear has died out.

The third [angle of the love-triangle is that] love is its own end. It can never be the means. The man who says, “I love you for such and such a thing”, does not love. Love can never be the means; it must be the perfect end. What is the end and aim of love? To love God, that is all. Why should one love God? [There is] no why, because it is not the means. When one can love, that is salvation, that is perfection, that is heaven. What more? What else can be the end? What can you have higher than love?

Judge people not. They are all mad. Children are [mad] after their games, the young after the young, the old [are] chewing the cud of their past years; some are mad after gold. Why not some after God? Go crazy over the love of God as you go crazy over Johns and Janes. Who are they? [people] say, “Shall I give up this? Shall I give up that?” One asked, “Shall I give up marriage?” Do not give up anything! Things will give you up. Wait, and you will forget them.

The ordinary Sannyâsin gives up the world, goes out, and thinks of God. The real Sannyâsin lives in the world, but is not of it. Those who deny themselves, live in the forest, and chew the cud of unsatisfied desires are not true renouncers. Live in the midst of the battle of life. Anyone can keep calm in a cave or when asleep. Stand in the whirl and madness of action and reach the Centre. If you have found the Centre, you cannot be moved.

First, meditation should be of a negative nature. Think away everything. Analyse everything that comes in the mind by the sheer action of the will.

Next, assert what we really are — existence, knowledge and bliss — being, knowing, and loving. Meditation is the means of unification of the subject and object. Meditate:

Above, it is full of me; below, it is full of me; in the middle, it is full of me. I am in all beings, and all beings are in me. Om Tat Sat, I am It. I am existence above mind. I am the one Spirit of the universe. I am neither pleasure nor pain.

The body drinks, eats, and so on. I am not the body. I am not mind. I am He. I am the witness. I look on. When health comes I am the witness When disease comes I am the witness. I am Existence, Knowledge, Bliss.

I am the essence and nectar of knowledge. Through eternity I change not. I am calm, resplendent, and unchanging.